It was just before dawn when I summited the 2,398' Mt. Constitution on Orcas Island, it's highest peak of the island and a view I had already visited two times previously since I started the Orcas Island 100 the previous morning. The early sun rays cut up from just below the horizon and painted the sky pink and orange—contrasted the muted clouds and blue sky. Despite the light, my third visit to Mt. Constitution was not a hopeful one.

“Despite the light, my third visit to Mt. Constitution was not a hopeful one.”

While climbing the brutal and unrelenting Powerline Trail minutes earlier I had convinced myself to quit as soon I got to the next aid station. It was done and decided. I had no specific injury, but was defeated by the previous 20 hours of struggle. Throughout the night I shivered in the sub-freezing temperatures compounded by strong gusts of wind ripping across island lakes and hilltops. That, and I couldn't stay awake for the life of me. At one point I laid down at the Mt. Pickett aid station and napped for 25 minutes next to a fireplace to try to recapture my spirit. Unfortunately this did little to bring my body or mind back to life.

"Maybe this race was just too early in the year?", I thought as I attempted to troubleshoot my failing body.

While I had run and completed 100-mile races before, they were all in the later summer. To train for my previous hundreds (and I've earned five buckles, ahem) I had competed in shorter races and ramped up my training to peak just at the right moment: August or September. As an early February race, my training for Orcas was entirely different.

Lacking the time or daylight to pack in many miles in December and January, I opted for a three prong approach to prepare my body and mind for the four 25-mile loops I knew I'd have to complete to earn my Orcas 100 buckle:

- Log weekend trail miles in my local stomping grounds of Issaquah, including hill repeats and treks up and down Mailbox Peak and Mt. Si.

- Ramp up my hot yoga from just a single class a week to 3 or 4 to build my core strength and maybe store some heat to use on race day (that's a thing, right?)

- Watch inspirational videos on YouTube by the Mulligan Brothers and this Will Smith clip. I love when he describes not being afraid to die on a treadmill. Smith hypothesizes that if he and someone else got on a treadmill together that he has the will to get off last, or die. Wow. There is something that I love about his intensity and that fatalistic dedication. I want to feel that commitment and mission!

I stuck with my training plan through December and January, counting down the weeks until race day. I knew Orcas 100 was going to be hard as I've run and completed the 50k version on the island three times before, but I didn't know how deep I'd have to reach. That is, until race weekend arrived.

The evening before the storm

The night before our start, all the runners assembled for a briefing at Camp Moran at the very far east end of Orcas. Ninety two friendly faces surrounded me, and listened intently as the race director, James Varner, read out updates on trail conditions, "Your feet will get wet", and reminded everyone to keep an eye out for course markers. I felt surprisingly relaxed and ready. The next morning, Friday, Feb. 9th I'd meet my "treadmill" challenge.

Before heading to bed, co-race director Elizabeth asked if I'd be open to capturing some GoPro footage from the trails and to being interviewed by KUOW, our local NPR station. "Of course" was my reply, always passionate for advocating for the trails.

Kara, a Web reporter, filmed a brief interview and inquired about my training from the past few months and goal for the run.

"To finish in less than 36-hours." I replied, stating the race cutoff time allotment. I wasn't being pessimistic, I just knew my goal was to finish and earn a buckle. Anything else would be gravy, or, Orcas mud.

High-five. Let's run.

On race morning I assembled with the other runners in the cool pre-dawn air. After a few unceremonious words, the adventure began. The first forty miles went as expected. I was conservative with my pace and aggressiveness, and listened to what my body needed: water, pickles, ginger ale, protein bars and more pickles. I tried to tune out with some music stored on my phone but never got into the flow, something that normally comes easy. Weird, but not disruptive.

As always the climb up the Powerline trail was tough. While it was by no means balmy, the sun had warmed up the cool moss just enough to cause sheets of steam to rise up from the ground. It was beautiful, and the perfect momentary distractions from the ascent.

But the promises of warmth were short lived. A few miles on while descending on a thickly-forested trail I was shocked by how cold it in the shadows, even during the middle of the day.

"It is going to be a cold night" I thought. And it was.

This is the first mountain race when I had to wear two pairs of gloves while moving at night: regular running ones covered by heavy snowboarding gloves. And sometimes this wasn't even enough to keep the chill out. During the early hours of Saturday I also layered on tights over my shorts and a lightweight shell pant over those to keep out the wind, or at least to try to. These layers did little to block the chill. For the life of my mountain running career I can't recall ever being that cold for that long. Hours of trying to stay warm while attempting to build warmth inside of my core. While the thermometer only said 30°F at its coolest, it felt so much colder. Maybe it was the wind or my emotions, but I was couldn't warm up.

You think you're quitting?!?

“I had hurt for the past 12 hours and I was just done. ”

By the time I got around to my third climb up Mt. Constitution, around mile 73, I had enough of the experience. I forgot all about Mr. Smith's inspiration, the steam I built up from hot yoga or my promise to NEVER come off the race course under my own will. I had hurt for the past 12 hours and I was just done.

But then something changed.

I saw Kara, the KUOW reporter, at the Mt. Constitution aid station where she had stayed up the whole night serving as the medic and capturing footage for her article. I saw my other friends bravely continuing down the trail from Mt. Constitution, starting their fourth and final loop. I saw the edge of the sun creep above the horizon and finalally light the sky after a long night. And I snacked on some jelly beans, too.

Hallelujah!

In that moment at the aid station my hope was restored. I would continue. I had 29 more miles to run, and 13 hours to do it. Even if I walked the entire thing. I knew my mission. But first I had to take my trek up the Tower Club.

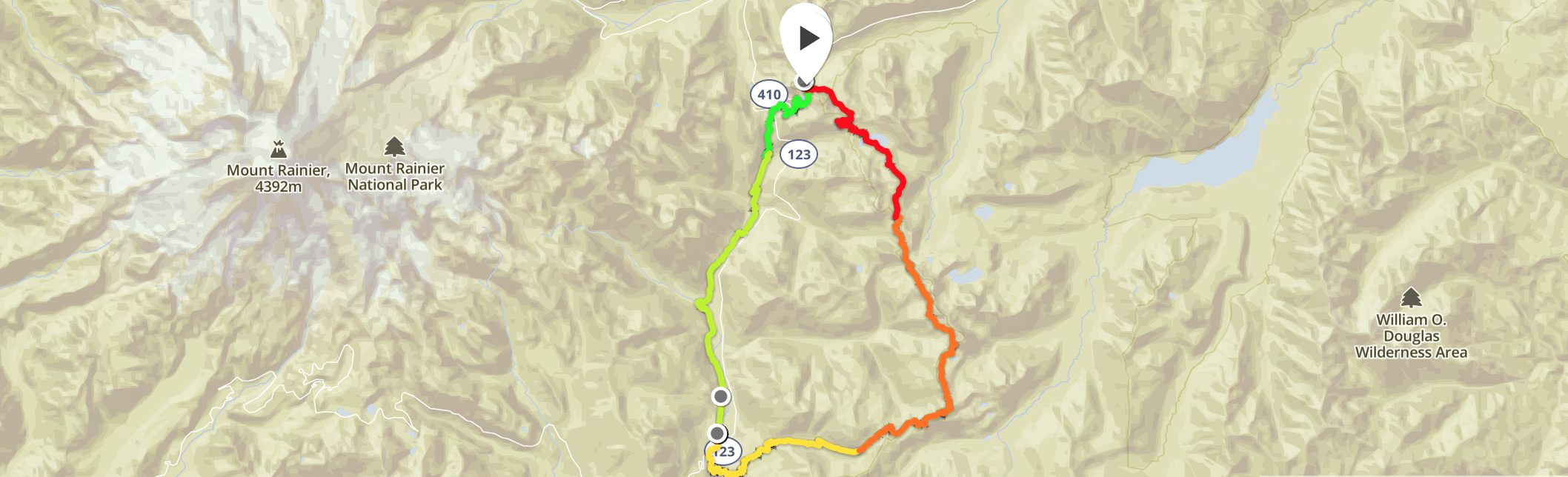

You see in addition to climbing 26,000' while running the 100-mile course, the wild beasts at Rainshadow Running were inspired to add yet another challenge to the event. For those who chose, runners could climb up the medieval-themed watch tower on top of Constitution as an added feat. To prove that runners ascended all the way to the top, race organizers left a hole punch which each of us used to add a mark to our race bib. One climb. One punch. Four climbs: and you're in the Tower Club, earning a special, dramatic shirt and odd bragging rights. While I was slow and recovering from my sleepiness, I couldn't resist the additional challenge (or sweet shirt).

That last loop was fun. One runner told me a secret: to curse and bid farewell each rock and tree you pass on the final loop, and that's exactly what I did. "!%$@ YOU, BRIDGE!", "#$@. YOURSELF, TREE!" It was sillygame, but a fun one that helps my final miles pass by.

While my forth loop of the course, now in the daytime, was neither my slowest or prettiest, I made it back up to Mt. Constitution one final time, took aid and then climbed the tower. After grabbing my final punch, I descended and ran down the trail as the sun set for a second time. I made it the final four miles back to Camp Moran a little over an hour later earning a time of 33:59:23. To my surprise, everyone eating and drinking at Camp Moran paused momentarily to cheer when I arrived, one of the last eight out of a total 69 2018 Orcas 100 finishers.

After grabbing a beer, I did a quick interview with Kara, and then spent the rest of the night listening to the live string band perform at Camp Moran and nursing my sore feet. I had earned my buckle. I had achieved my goal. And most importantly, I had not betrayed Will Smith.

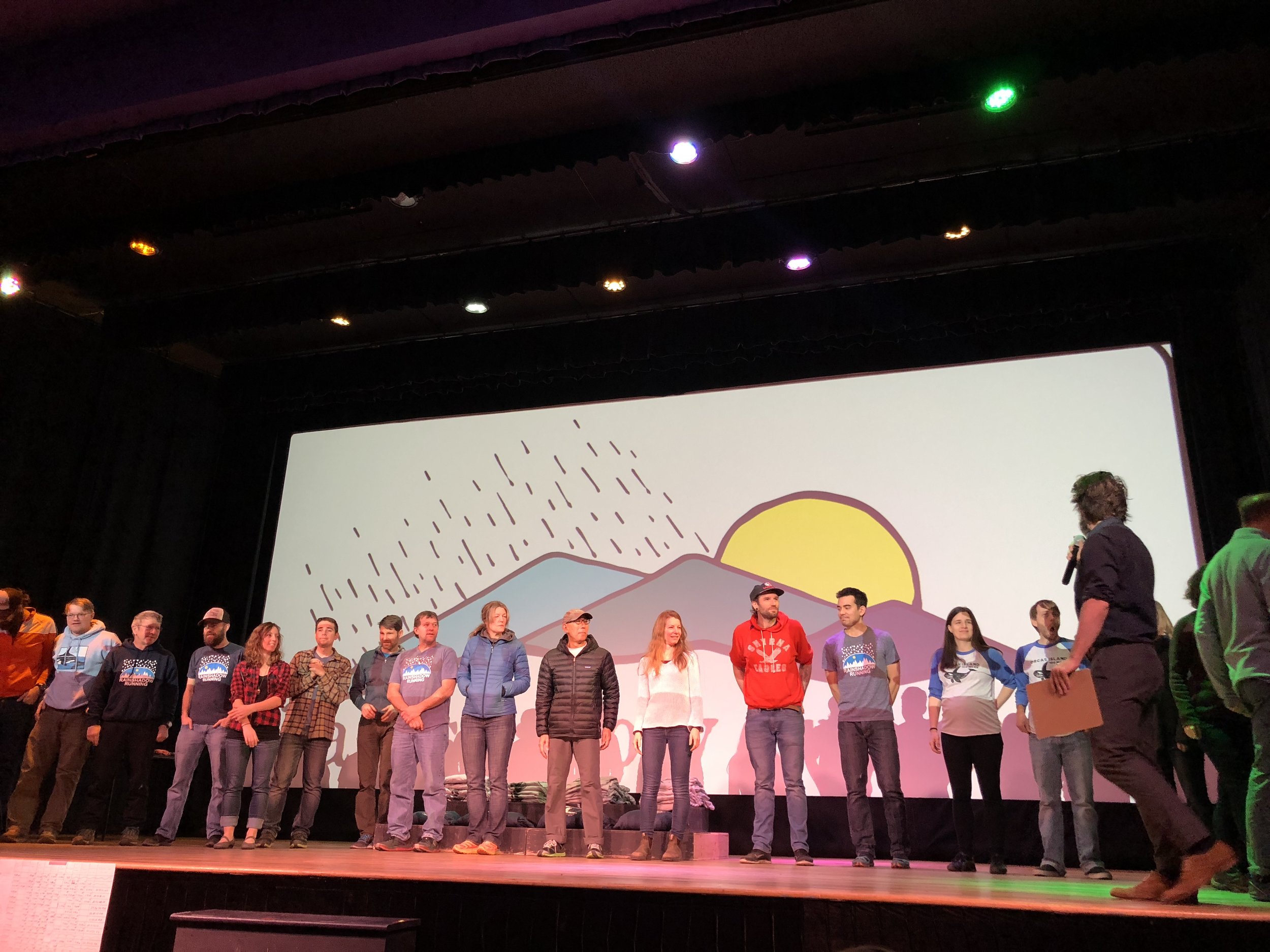

But in all seriousness, thanks does not go to YouTube motivational videos or celebrity rappers, but to the race organizers and volunteers who braved tough weather to host a challenging race for just 92 runners, and 69 finishers. You are strong, kind and caring people. Thank you for letting me touch the darkness and make it back.

A few days later Kara published her dramatically-titled KUOW article "What 100 miles of misery looks like" and video. While in truth for me it was probably only about 35-miles of true misery, I thought she perfectly captured the spirit of the event. I was thrilled to hear that Kara was so inspired by the Orcas event that within days she signed up for her first, trail race. Beautiful!

My goal was to finish Orcas and I was able to achieve that. Even more than gratified, I feel grateful to those who helped me make it back from the darkness.

While it was one of last year’s

While it was one of last year’s

After it was all said and done, I counted exactly

After it was all said and done, I counted exactly